Zero to hero

AQA’s English Language GCSE is generally regarded as being a tricky exam to prepare students for, with many finding Question 3 of Language Paper 1 a particular bugbear to respond to. So much so, in fact, I’ve heard from several Year 11 students recently who opted to skip this question entirely in their mock exam, happy to forfeit the 8 marks so they could re-invest their time on the paper’s other questions.

How has it come to this?

The mark scheme for Question 3 states that students are asked to analyse ‘the effects of a writer’s choice of structure’. As a guide, AQA recommends students to consider some key questions of the text, including:

1. When I first start to read the text, what is the writer focusing my attention on?

2. How is this being developed?

3. What feature of structure is evident at this point?

4. Why might the writer have deliberately chosen to begin the text with this focus and therefore make use of this particular feature of structure?

This is all very well, until we get to that fourth question. Generally, I can get students to notice one thing changing to another thing. But the moment the wheels come off is when I ask a class ‘Why is it interesting?’ ‘Why might the writer have done that?

More often than not, I’m met with blank faces.

I too have found myself making impressive cognitive leaps in the classroom to arrive at something interesting to say about the sudden shift from, say, description to dialogue or why the writing describes a broad panoramic landscape and then settles on some minute description. It’s really hard to think of something reasonable to say and can feel very much like, well, guessing.

Many generous folks on Twitter/X have painstakingly made resources to help teachers get theirs heads around this question. A simple search will reveal dozens. One good example even comes from AQA itself in this ‘Further Insight Series’ document that provides some concrete examples of what an examiner would look for: https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/english/AQA-87001-Q3-FI-HSA.PDF

It includes a top-level, full-mark response using an extract from the novel City of the Beasts by Isabel Allende, a copy of which can be found here: Paper_1_insert_Alex_.pdf (oasisacademybrightstowe.org).

Here is the model response provided by AQA to demonstrate the sort of answer that would get full marks:

The text focuses on a character called Alex Cold, and the reader get to see him from two different angles. At the beginning he is alone in his bedroom and waking up from a nightmare where his mother was carried off by ‘an enormous black bird’. Then in the second half of the text the writers changes the focus to Alex being with the rest of the family downstairs at breakfast time. He is snappy with his sisters when Andrea says ‘Mamma’s going to die’. This links the two halves of the text together because the fear Alex experiences in the earlier nightmare is now manifested at the breakfast table. Shouting at his sisters makes it seem as if he disagrees with her, but because the reader has already has an insight into Alex’s subconcious mind, we understand at the this point that really it’s the opposite. He shouts at his sister because secretly he fears what she is saying is true and his mother might really die.

In the final two paragraphs we are deliberately presented with a direct contrast between Alex’s parents. First, the focus narrows from the whole family onto Alex’s father, who is struggling to look after the children. There is nothing in the refrigerator but orange juice and they are living on takeaway food. Then the final paragraph zooms in on both then and now versions of the mother. It begins with the sentence ‘Alex had realised during those months how enormous their mother’s presence had been and how painful her absence was now’. This structure is effective because by first showing how inadequate his father is, even though it’s not his fault, it therefore emphasises how wonderful the mother is, or at least used to be. In a way, this also make me re-evaluate the nightmare at the beginning because we have seen for ourselves the close bond between Alex and his mother and now understand why it ‘startled’ him so much and why he experienced ‘pounding in his heart’, a physical reaction to the fear of losing her.

How structure is assessed, Paper 1, Question 3 , Further insight series, AQA

This model response picks up on shifts in focus, then contrasting characters, and finally a noticeable shift from the beginning to the ending.

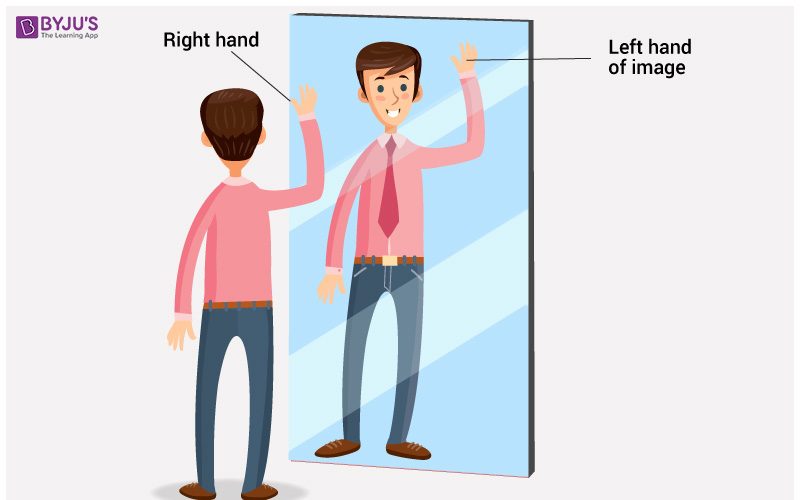

What this model answer appears to suggest is that the extract is to be read and understood in a vacuum, as if all the information a students needs to draw from is written on the page in front of them. An issue with this, as far as I can see, is that no single structural feature is ever really all that inherently interesting. Structure itself does not really create meaning, but can become of interest in the way it works in conversation with the wider traditions of storytelling.

As E. D. Hirsch attests to in his book Cultural Literacy ‘to grasp the words on the page we have to know a lot of information that isn’t set down on the page’.

My gripe with the example provided by AQA is that it does not appear to be addressing anything to do with the tradition of storytelling structures, encouraging (it seems to me) an analysis of the structure using only what is set down on the page – a frustrating task, as this isn’t what skilled readers do.

Alex Quigley, in a 2022 blog post titled ‘Developing Skilled Readers’ argues: “knowledge of stories, and their structures, complex patterns of characters, themes, and language […] proves vital to the entire story. As such, the ability of pupils to make meaningful predictions, and to comprehend what they read, rests upon a sea of background knowledge.”

What background knowledge might help?

In order for students to be ‘skilled readers’, as Quigley says, they could be taught typical story structures, such as Christopher Booker’s ‘Seven Basic Plots’, summed up nicely here: Story Archetypes: How to Recognize the 7 Basic Plots – 2024 – MasterClass.

To make matters slightly simpler, these archetypes are (broadly-speaking) variations of the so-called ‘hero’s journey’ storytelling structure, set out in Joseph Campbell’s book The Hero With a Thousand Faces (a detailed explanation of which can be found here: The 12 Steps of the Hero’s Journey, With Example | Grammarly)

Students will often already have an understanding of these structures seeing as how they underpin big franchises like Harry Potter, The Hunger Games or Star Wars. That said, students may not be entirely clear how, so explicit teaching of what the hero’s journey is and how writers play with it in interesting ways is important.

Bearing this backgound knowledge in mind, then, here is a response I wrote to the same question, imagining what a student with working knowledge of the hero’s journey might say:

The story of Alex Cold appears to borrow strikingly from the storytelling archetype ‘the hero’s journey’, opening with what appears to be the story’s main conflict: the character of Alex Cold needing to heroically overcome a monster in the form of an ‘enormous black bird’, a figurative representation of his mother’s death. By presenting not only the monstrous bird in the dream, but also a setting filled with ‘shattered glass’ the encounter between Alex, as the story’s hero, and this monster, takes place in the suitably uncanny setting of a dream. Here, interestingly, it suggests that Alex is poised between two states: on the one hand he is still firmly at home, his dream taking place in the relatively familiar setting of his family’s ‘house’, the monster too taking the familiar form of a ‘bird’. However, he is crossing a threshold into an unknown world – his home’s window being ‘shattered’, the bird is ‘enormous’, the ocean ‘roars’. In this sense we are being presented with Alex arguably in a state of limbo, refusing the heroic call due to what appears to be fear.

Alex then wakes from the dream to a ‘large dog sleeping beside him’ a place of comforting familiarity. But this too appears uncanny as if Alex is still ‘tangled in the images of his bad dream’. The family eat breakfast, but pancakes, a homely staple, now seem strange ‘like rubber-tyre tortillas’. Likewise, the other characters of Alex’s family, a symbol of order, are in a state of chaos, ‘shriek[ing]’ at one other only to be ‘interruped, without much conviction’ by their father.

The extract concludes with a memory of the more orderly past, a ‘house immaculate’, serving as an insight into the potential reward that will come once Alex finds the bravery to come to terms with his mother’s death. There is the impression that Alex will achieve this, as foreshadowed by this memory, but to do so he must face the monstrous challenge head on so that he can benefit not only himself, but also his family, who will altogether be transformed back to a state of order by this experience.

Like the example provided by AQA, I too have worked through the extract chronologically, concentrating on shifts in focus. The difference being that by looking at the text through the mental model of the hero’s journey, I can see that the writer’s structural choices are a consequence of them playing with a storytelling tradition, a far interesting means of reading the text than just looking shifts from one thing to another for the effect of emphasis.

Armed with this knowledge, the exam question becomes a clearer, more straightforward task that students can actually study for, and – significantly – an opportunity of them to actually grapple with the disciplinary knowledge of the subject.

Explicit teaching of storytelling structures, like the hero’s journey, would ideally happen at Key Stage 3, and not left until Key Stage 4. I have seen some wonderful curriculums that aim to embed this sort of knowledge early on in secondary school, such as the OAT English curriculum project: OAT English (ormistonacademiestrust.co.uk)

I’ve been teaching the ‘hero’s journey’ to my students recently who I daresay have found it fascinating. They have enjoyed unpicking stories they have known for many years, but weren’t aware of how they converse with a tried and true storytelling archetype. And they have found it working away in the background of our literature texts too: Macbeth, An Inspector Calls, Jekyll and Hyde, even some of the Love & Relationships poetry, enabling them to offer fascinating new interpretations.

For an English teacher, at least, what could be more interesting than that?